Question Types on the AP World History: Modern Exam

April 9, 2024

The AP World History: Modern exam is a 3-hour and 15-minute exam that tests your ability to think like a historian. It will ask you to analyze primary and secondary sources and identify patterns and connections that can support a historical interpretation. This AP exam will also test your knowledge of historical concepts covered in the AP World History: Modern course. Before taking the exam, review the types of questions you’ll encounter so you get comfortable with the format and know how to manage your time. Practice answering sample questions, like the ones below, and understand how the exam is graded, especially the free-response questions, to maximize your exam score. In this guide, we break down what you need to know about the four question types on the AP World History: Modern exam.

What are the Four Question Types on the AP World History: Modern Exam?

There are four types of questions on the AP World History: Modern exam, including multiple-choice questions, short-answer questions, and free-response (essay) questions. The free-response questions are composed of a document-based question (DBQ) and a long essay question (LEQ). In the first half of the exam, you will have 55 minutes to complete 55 multiple-choice questions. Immediately following, you’ll answer three short-answer questions in 40 minutes. The second half exam gives you 100 minutes to answer both the DBQ and LEQ.

Multiple-Choice Questions on the AP World History: Modern Exam

The first part of the AP exam requires you to answer 55 multiple-choice questions in 55 minutes. This section of the exam is worth 40% of your total exam grade.

Each multiple-choice question on the AP World History: Modern exam includes four answer options; you will pick the one that BEST answers the question. These questions will be grouped in approximately fifteen to twenty clusters, typically of three or four questions. One point is awarded for each correct answer. Incorrect answers are not penalized, so answering all the multiple-choice questions is important even if you have to guess.

Expert tip: Start by eliminating incorrect answers. Every distractor, or wrong answer, is supposed to sound somewhat plausible. Still, a quick but careful reading generally allows you to eliminate at least one wrong answer if not two. This is the first thing you should do. If you can quickly pick the correct answer from the two or three that remain, do so. If you can’t, flag the question and return to it during your second run through the exam.

[ LISTEN: Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 9: “Multiple-Choice Questions” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Multiple-Choice Question

The following is a sample multiple-choice question similar to one you might find on the AP World History: Modern exam. In this example, you must read the following excerpts and use them to answer the question below.

The story of my great-grandmother was typical of millions of Chinese women [before the 1911 revolution]. She came from a family of tanners. Because her family was not intellectual and did not hold any official post, and because she was a girl, she was not given a name. Being the second daughter, she was simply called “Number Two Girl.” [She never met her husband] before her wedding. In fact, falling in love was considered shameful, a family disgrace. Not because it was taboo, but because young people were not supposed to be exposed to situations where such a thing could happen, partly because it was immoral for them to meet, and partly because marriage was seen above all as a duty, an arrangement between two families. With luck, one could fall in love after getting married.

from Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (1991)

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. This truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

from Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

- The observations made in the above quotations are best understood in the context of which of the following?

a. The use of religious doctrine to regulate the role of women in society

b. The impact of industrialization on family structures

c. The oppression of women due to the rise of social Darwinist ideologies

d. The shaping of marriage customs by prevailing social and economic norms

Check your answer.

Answer: (D) Contextualization and process of elimination help to answer this question. Neither quotation speaks directly to religion or industrialization, making A and B unlikely. While oppression is evident in the first quotation, it is not overtly so in the second, and has nothing to do with social Darwinism in any case, so C is incorrect. In both cases, but in different ways, the impact of social and economic factors on marriage is at stake, and those are what tie the questions together.

Short-Answer Questions on the AP World History: Modern Exam

After finishing the multiple-choice section, you’ll answer three short-answer questions. You will have 40 minutes to complete this section of the test, giving you roughly 13 minutes to answer each question. This section is worth 20% of your total exam grade.

The short-answer questions will ask you to use content knowledge and various historical skills to provide written responses to three short-answer questions. You must complete the first and second questions; you will then have the choice to complete the third or fourth.

- Short-answer questions #1 and #2: These questions can cover any time period between 1200 and the present. The first question will require you to assess some sort of secondary source, and the second will test you on primary source material.

- Short-answer questions #3 and #4: These questions will not provide any specific stimulus material. The third question will cover the period from 1200 to 1750, and the fourth will focus on the years between 1750 and the present.

Each short-answer question will ask you to do three things, each of which will be worth one point. You are not required to develop a thesis for the short-answer questions. Your main strategy should be to complete all three questions within the set amount of time and to clearly indicate that, in each case, you have satisfactorily accomplished all three goals. Lengthy answers are unnecessary — one long paragraph, or perhaps two or three short paragraphs, should suffice.

[ LISTEN: Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 10: “Short-Answer Questions” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Short-Answer Question

Below is an example of a short-answer question similar to one you will encounter on the AP World History: Modern exam. Use the two passages below to answer all parts of the question that follows.

It is nowadays common for Indian history textbooks to treat the various “empires” that successively occupied the stage of Indian history as so many successive repetitions with merely different names for offices and institutions that in substance remained the same: namely, the King, the Ministers, the Provinces, the Governors, and so on. But D.D. Kosambi, in his Introduction to the Study of Indian History, rightly observed that this repetitive succession cannot be assumed, and that each regime, when subjected to critical study, displays distinct elements. We know most, of course, about the Mughal Empire, which displays so many striking features. In its large extent and long duration, it had only one precedent, in the Mauryan Empire, some 1,900 years earlier. Some scholars regard it as the fulfillment of the political ambitions embodied in Indian polity for three millennia. And yet there is also a temptation to see in the Mughal Empire a primitive version of the modern state. Its existence belongs to a period when the dawn of modern technology had occurred in Europe, and some of the rays of that dawn had also fallen on Asia. Can it then be said that the foundations of the Mughal Empire lay in artillery, the most brilliant and dreadful representative of modern technology, as much as did those of the modern absolute monarchies of Europe?

M. Athar Ali, “Towards an Interpretation of the Mughal Empire,” 1978

The prevailing view of the Mughal Empire has been based on the mistaken assumption that this state was a kind of unfinished, unfocused prototype of the British Indian Empire of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A more fruitful approach is to treat the Mughal Empire as one example of the [older-fashioned] patrimonial-bureaucratic empire, featuring a depiction of the emperor as a divinely-aided patriarch, the household as the central element in government, members of the army as dependent on the emper – or, the administration as a loosely structured group of men controlled by the imperial household. It seems clear that to accept this interpretation of the empire is to accept the necessity of re-examining the entire structure of Mughal political activity.

Stephen P. Blake, “The Patrimonial-Bureaucratic Empire of the Mughals,” 1979

- Using the excerpts above, answer (a), (b), and (c).

a. Provide ONE piece of historical evidence (not specifically mentioned in the passage) that would support Ali’s interpretation of the Mughal Empire’s fundamental nature.

b. Provide ONE piece of historical evidence (not specifically mentioned in the passage) that would support Blake’s interpretation of the Mughal Empire’s fundamental nature.

c. Explain ONE way in which the views about Mughal governance expressed in the two passages led the authors to propose different interpretations of the empire’s fundamental nature.

Check your answer.

Possible answers:

The scholarly debate at stake here is whether the Mughal Empire is best seen as the product of early political modernization—and a departure from earlier regimes ruling India—or as a government that followed older patterns of rulership. Ali promotes the first argument, while Blake, using the label “patrimonial” (in which the state is considered the personal property of a monarchical ruler), takes the second position. The easiest way to answer Part A is to mention the Mughal Empire’s success as a “gunpowder empire,” along with Ottoman Turkey, an adoption of modern technology that buttresses Ali’s thesis. One could also discuss the empire’s elaborate bureaucracy, much of which was in fact kept in place by the British as they extended their colonial reach over India. In favor of Blake’s argument in Part B, one could easily mention how religious policy—especially pertaining to Muslim rulership over India’s Hindu majority—varied widely based on the personal preferences of any given emperor, from Akbar’s remarkable tolerance to Aurangzeb’s extreme Islamic rigidity.

In explaining the differences between the two views, as Part C requires, it might be tempting to point to the two authors’ national differences, one being Indian, the other not. However, the debate does not seem to revolve around this question. Even though one might be able to say that patriotism inclines Ali to favor an argument depicting Mughal India as more modern than Blake appears to think, highlighting this sort of difference in this case runs the risk of stereotyping national viewpoints. (Still, be aware that national perspectives will sometimes affect debates of this type, especially when it comes to Western imperial treatment of other parts of the world, so in some instances it could be worth bringing up.) Perhaps the best way to answer this part of the question would be to point out that Ali seems mostly concerned with the Mughal Empire’s place as a particular stage in India’s long history, while Blake is mainly interested in the Mughal Empire as a political system typical of its era and in comparison with other regimes in Eurasia during a particular time.

Free-Response (Essay) Questions on the AP World History: Modern Exam

The free-response section of the AP World History: Modern exam lasts 100 minutes and consists of the document-based question (DBQ) and the long essay question (LEQ). The section begins with a 15-minute reading period, during which you are allowed to read both questions, examine the DBQ documents, and plan your responses (taking notes and making outlines). Alternatively, you can start writing immediately. Either way, you can write the essays in whichever order you wish, and you can use the time however you please. We suggest using the 15-minute reading period to read the documents and outline your answers. The rest of the time should be divided more or less evenly, with perhaps 45 minutes spent on the DBQ and 40 minutes on the LEQ.

A commonly followed guideline is to write the DBQ first. The documents will be fresh in your mind, and because the DBQ operates according to the most complicated rules, it will be good to have it out of the way. Just make sure to leave enough time for the LEQ! Practice writing essays in 40 minutes or less to improve your time management skills for this section.

The Document-Based Question on the AP World History: Modern Exam

Unlike the other essays, the DBQ on the AP World History: Modern exam asks you to perform well on two fronts. Not only does the essay itself have to be well written (complete with a good thesis), but you must demonstrate skillful handling of the seven documents. The DBQ is worth 25% of your total exam score.

The DBQ will focus on some time period between 1450 and the present. When taken together, the documents address a particular theme or issue, typically with a fairly narrow focus when it comes to era, geography, and topic. For example, a DBQ might ask about industrialization in nineteenth-century Asia or European imperialism in a specific part of the world. Or it might ask about a noteworthy cultural trend, technological innovation, trade network, or sociological development.

A DBQ will tie your use of the documents to one of several historical reasoning skills. You may be told to compare and contrast two things, to trace continuity and change over time, or to analyze causes and consequences. You will organize the documents into groups (typically three of them) and discuss the documents’ context as well as their creators’ point of view or purpose. To test your understanding of how documents can sometimes be of limited usefulness, the DBQ will ask you to identify additional evidence that, if provided, would shed further light on the question.

Expert Tip: Vague language equals a weak thesis! Be as specific as possible—but without getting swamped. Your thesis shouldn’t be too long or contain too much detail.

[ LISTEN: Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 11: “The Document-Based Question” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Document-Based Question

Use Documents 1–7 to answer the following sample document-based question.

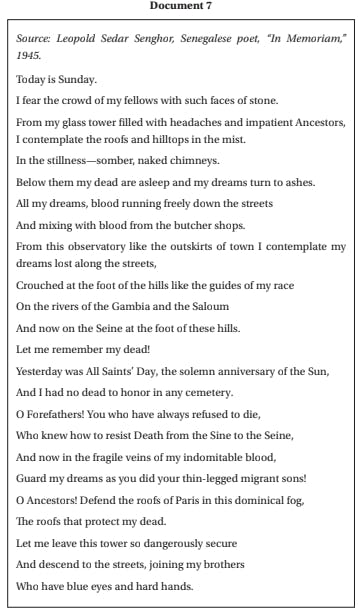

- Evaluate the extent to which Pan-Arabism and Pan-Africanism have differed in their nature and political effectiveness in the modern era.

Check your answer.

During the global wave of decolonization that followed the end of World War II, two political ideologies seemed poised to gain permanent prominence: Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism. Both movements followed the same logic, attempting to empower previously colonized peoples by encouraging a sense of unity based on broad cultural and ethnic identities, rather than on narrow national ones. A key difference, however, is that Pan-Africanism defined itself mainly in terms of opposition to racial and colonial oppression, whereas Pan-Arabism was in a better position to appeal to a common linguistic and religious heritage. In the end, while both achieved certain successes, both proved weaker than the lure of traditional nationalism and fell far short of their original aspirations.

Pan-Africanism had deeper roots than Pan-Arabism, and much of it sprang from the discontent felt by African-descended populations who lived among abusive white majorities or under white colonial rule. These experiences are spoken of by the 1920 “Declaration of the Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World” (document 4) and the 1945 poem “In Memoriam,” by Leopold Senghor (document 7). Senghor, from the French colony of Senegal, describes the alienation he feels living in Paris, surrounded by French whites—supposedly his “brothers,” but completely different, and to be feared, with their “faces of stone,” “blue eyes,” and “hard hands.” The contrast between his native landscape and holidays with the streets of Paris and the Catholic Day of All Saints reminds him that he does not belong. As a central figure in the negritude movement, Senghor stressed African identity as a source of strength for all those of African descent living under white rule, no matter where or under which colonial authority. The same viewpoint was expressed even more forcefully by the delegates to the 1920 Convention of the Universal Negro Improvement Association in New York City. The idea here was that all those of African descent shared a common problem— white oppression, whether in the United States, the Caribbean, Europe, or Africa itself under colonial rule—and a common heritage, and should therefore band together, regardless of language or specific tribal origin. The Convention’s “Declaration” went so far as to nominate an actual president of Africa, and to designate a song about Ethiopia as its anthem.

Document 2, an essay from the 1960s by Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere, carries the Pan-African vision into the post-World War II era, when many African nations overthrew colonial regimes or were in the process of doing so. Along with Kwame Nkrumah, who won freedom for Ghana from British rule, Nyerere was one of this time period’s most outspoken supporters of Pan-Africanism. (Also like Nkrumah, Nyerere can be viewed in the larger context of “Third World” political leaders such as Sukarno of Indonesia, Nehru of India, and Nasser of Egypt, all of whom sought ways to strengthen their newly liberated countries and keep them free of Western political interference and economic domination.) Nyerere identifies a key “dilemma” of Pan-Africanism: the fact that African independence has to be achieved country by country, after which it is tempting for each country to focus narrowly on its own interests. He argues vehemently that Africa can prosper only if such temptations are overcome in favor of a larger, more cooperative understanding of what it means to be African. The mural pictured in document 5 is a visual representation of this utopian ideal, which seeks to unite a billion people under one inclusive label, bridging all other ethnic or linguistic differences. Neither document, however, sufficiently addresses the huge difficulties involved with uniting peoples as diverse as those in Africa actually are. While politicians like Nyerere and Nkrumah managed to establish transnational organizations like the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union), conflict and disunity have tended to greatly outweigh Pan-African unity in the decades since World War II. Differences in language, ethnic and tribal identity, and local culture and religion seem to have proven stronger than abstract ideology.

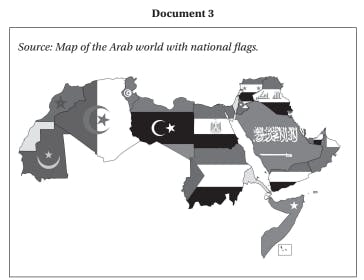

Documents 1, 6, and 3 all have to do with Pan-Arabism. Gamal Nasser, who had just risen to power in Egypt as a nationalist leader, and would outrage much of the West by establishing Egyptian control over the Suez Canal, ranks with Nyerere as a major political figure in the “Third World” during the 1950s and 1960s. Like the Pan-Africanists, Nasser saw Pan-Arabism as a means to build strength and defy the militarily stronger and more economically prosperous nations of the West. To that end, he even managed to join Egypt to Syria and Iraq in a short-lived United Arab Republic. Much more so than Pan-Africanism, Pan-Arabism had the potential to foster transnational unity, because most people in the so-called Arab world shared a common language (Arabic), a common history and cultural heritage, and, in most cases, a common religion (Islam). Document 6, a recent newspaper editorial, makes this exact point in calling for a revival of the Pan-Arab ideal in order to preserve Arab identity in the face of westernization. However, the fact that document 6 has to call for Pan-Arabism in 2012 clearly indicates that, even with the advantage of a common tongue and heritage, Pan-Arabism—like Pan-Africanism—yielded few concrete political results. Some of the region’s smallest nations may have fused together as the United Arab Emirates, but this is hardly a political powerhouse. Document 3, a graphic showing the “Arab world,” with each nation linked to its individual flag, does not say anything overtly—but by its very nature speaks to the failure of Pan-Arabism to overcome national differences in favor of a larger regional identity. Like Nkrumah and Nyerere, Nasser failed to cement in place a larger dream of union.

As rich as the current selection of documents is, you should include additional perspectives to shed even more light on this comparison between Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism. While political elites are well represented, the point of view of nonstate actors is not, and there is much historical evidence to show that the concerns of most ordinary people tend to be local or national, and rarely transnational. Even political leaders who theoretically supported Pan-Arabism, like Gaddafi in Libya and Nasser himself, cared more for their own nations’ interest in the end. With respect to Africa, numerous episodes—such as the Biafra War (in which the Igbo minority tried to secede from Nigeria in the late 1960s) and the 1994 genocide committed in Rwanda by the Hutu against their Tutsi neighbors—provide evidence of the real-life difficulties involved with realizing the dream of Pan-African unity. Finally, to contextualize this topic even further, it would be useful to compare it with trends in Asia during this period. There, too, especially in South and Southeast Asia, many nations decolonized, and a number of them tried to form transnational coalitions or alliances. While Pan-Asianism was not attempted to the same degree that Pan-Arabism and Pan-Africanism were, organizations such as the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) emerged to accomplish at least some of the same things that Pan-Africanists and Pan-Arabists hoped to bring about in their own regions.

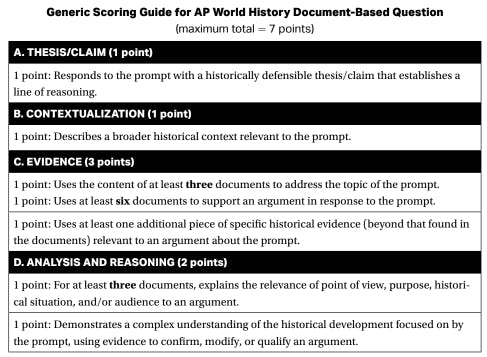

How is the Document-Based Question Scored?

The table below shows the official AP scoring guide for the DBQ. The maximum score you can receive is a “7.”

The Long Essay Question on the AP World History: Modern Exam

The AP World History: Modern exam’s long essay question (LEQ) asks you to develop and support an argument based on evidence. Although you can write this essay before the DBQ if you wish, we recommend you save it for last because of the DBQ’s complexity. Aim to spend about 40 minutes on the LEQ.

You’ll choose between three LEQs. Be sure to select the one you feel the most confident in answering. All three options will test the same historical reasoning skill and focus on the same course theme but cover a different time period: the first will cover 1200–1750, the second will focus on 1450–1800, and the third will do the same for 1750 to the present. The reasoning skill will vary from year to year, rotating through causation, comparison, and continuity/change over time.

[ LISTEN: Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 12: “The Long Essay” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Long Essay Prompt

Below are three sets of questions, each reflecting how the AP exam, in any given year, might target a particular historical reasoning skill and course theme. One sample answer—responding to one of the comparison questions—is provided.

Directions: Answer Question 1 or Question 2 or Question 3.

Possible Comparison Questions (Course Theme = State Building)

- In the period 1200 to 1500, states in Europe and in India used various techniques of conquest and rulership to consolidate and centralize their authority. Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which states in each region succeeded in their goals of political consolidation and centralization.

- In the period 1450 to 1800, the Ottoman Empire and China employed various strategies to legitimate their political authority. Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which each state succeeded in this goal.

- In the period after 1900, both Latin America and the Middle East significantly modernized their political systems. Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which this process was accomplished in each region.

Check your answer to Question #3.

The first half of the twentieth century brought immense changes to many parts of the globe. Among these was increased modernization in a number of non-Western regions, including Latin America and the Middle East. Both places faced similar obstacles, such as relative socioeconomic backwardness, heavy influence from outside powers, and limited success in the past with representative government. There were, however, key differences as well. Latin American states, with their generally longer history of independence, tended to be more modern already. Traditional religion was less of a barrier to change in Latin America than in the Middle East, and events like the world wars and the Great Depression affected both areas differently. On the whole, these differences outweighed the similarities, causing Latin America to make more progress toward modernization than the Middle East.

At the beginning of this period, both Latin America and the Middle East suffered from social and economic underdevelopment. Wealthy elites, whether colonial, corporate, or royal and aristocratic, benefited from the unbalanced exploitation of a handful of commodities. In Latin America, these included foodstuffs (beef, coffee, bananas, and other fruit) and natural resources such as copper, steel, fertilizer, and, in some countries, oil. Oil was even more central to the economies of the Middle East, just as it is today. This “banana republic” overexploitation of resources discouraged the healthy diversification of economies and kept societies rigidly stratified, with small upper classes dominating large, impoverished majorities. Although some of this changed between 1900 and 1945, it limited modernization throughout the period.

Another similarity is that Latin American and Middle Eastern states tended to be heavily influenced by outside powers, both before and during this half century. Prior to World War I, much of the Middle East was ruled by the Ottoman Empire or fell into European spheres of influence—and even though the Ottomans fell after WWI, European spheres of influence grew even larger when the post-WWI mandate system placed much of the Middle East, especially the Ottomans’ former Arab possessions, under French and British custody. Most Latin American states had been free since the wars of independence of the early 1800s, but foreign investors (like America’s United Fruit Company) wielded much power over Latin American governments, and the U.S. government regarded the region as part of its political sphere of influence. The Pan- American Union and even Franklin Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy were instruments of U.S. diplomatic interests throughout Latin America. Even when these outside interests did not deliberately oppose modernization (and they often did), it was rarely in their interest to actively support economic diversification, and because dealing with cooperative elite classes was easier than negotiating with elected governments representing a range of popular interests, they did not necessarily support democracy either.

On the other hand, important differences moved Latin America further down the path toward modernization. To begin with, Latin American states, while nonindustrialized by the standards of Western Europe and North America, had undergone more industrialization than most parts of the Middle East. With this kind of foundation to build on, countries like Mexico and Argentina, for example, found it easier to create sizable industrial sectors after WWI. Latin American states also had a tradition of constitutional rule stretching back to the era of Simo'n Bol var in the early 1800s, and while those constitutions were not always perfectly followed, they created a more favorable climate for progress when it came to gender equity, enlarging the middle classes, and reforming electoral systems. Less of this was possible in the Middle East.

Another crucial difference involves the role of religion. Although Catholicism was overwhelmingly central to Latin American culture, and although it tended to exert a conservative influence over public life there, by this point in history it was not nearly as much a barrier to social and economic progress as traditional Islam still was in the Middle East. It is no coincidence that the Middle Eastern states that modernized most were the small handful where energetic westernizing autocrats—most famously Mustafa Kemal Ataturk of Turkey and Reza Khan Pahlavi of Persia (Iran)—defied the will of Muslim clerics, secularized their states, industrialized their economies and educational systems and, in Ataturk’s case, gave women the vote. By the early twentieth century, such fierce conflict with institutional religion was far less necessary for Latin America to modernize. In the Middle East, by contrast, it remains a struggle even today to balance modernization with respect for Islamic tradition.

Another comparison to consider is the prevalence of dictatorship in both regions during these years. Whether they were monarchs or autocratic strongmen, authoritarian leaders in both regions were often the agents of modernizing change. In the Middle East, the primary impulse for economic and social modernization was typically the will of determined authoritarians, such as the above-mentioned Ataturk and Pahlavi. Among the Latin American dictators who promoted industrialization and other modernizing changes were the Perons in Argentina and the Vargas government in Brazil. One last point that calls out for attention is the pronounced trend toward authoritarian rule worldwide during this period. A truly contextual view of this topic must take into account the rise of dictatorial or nondemocratic regimes in places like Asia (Japanese militarism during the 1930s, warlords and Chiang Kai-shek in China after the collapse of Sun Yat-sen’s democratic revolution) and Europe (most notably Lenin and Stalin in Russia, Mussolini in Italy, and Hitler in Germany). As with the regions discussed more directly by this question, dictatorship in these other places arose in some cases due to political and economic crises like the Depression, and in other cases due to pressures brought about by rapid modernization.

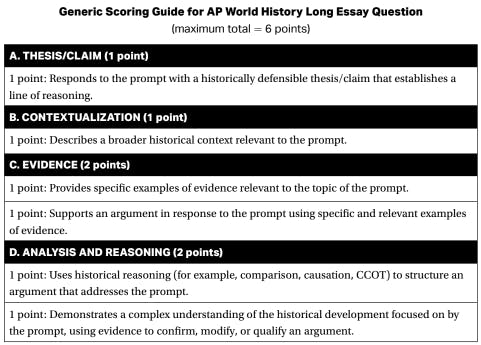

How is the Long Essay Question Scored?

The LEQ is less complicated than the DBQ, but certain tasks need to be accomplished the right way to earn a maximum score of six points. Below, we break down the scoring guide for the AP World History long essay question.

AP Biology Resources

- About the AP Biology Exam

- Top AP Biology Exam Strategies

- Top 5 Study Topics and Tips for the AP Biology Exam

- AP Biology Short Free-Response Questions

- AP Biology Long Free-Response Questions

AP Psychology Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP Psychology Exam?

- Top 5 Study Tips for the AP Psychology Exam

- AP Psychology Key Terms

- Top AP Psychology Exam Multiple-Choice Question Tips

- Top AP Psychology Exam Free Response Questions Tips

- AP Psychology Sample Free Response Question

AP English Language and Composition Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP English Language and Composition Exam?

- Top 5 Tips for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- Top Reading Techniques for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- How to Answer the AP English Language and Composition Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Sample Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Multiple-Choice Questions