AP U.S. History Notes: Period 7

April 12, 2024

AP U.S. History Period 7 covers a critical period in U.S. History, including World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II. Maximize your AP test prep with APUSH Period 7 study notes and get an overview of what happened in Period 7 of APUSH, along with key exam topics and essential vocabulary. Looking for more APUSH test prep resources? Check out Barron’s AP U.S. History Premium Test Prep Book and our AP U.S. History Podcast.

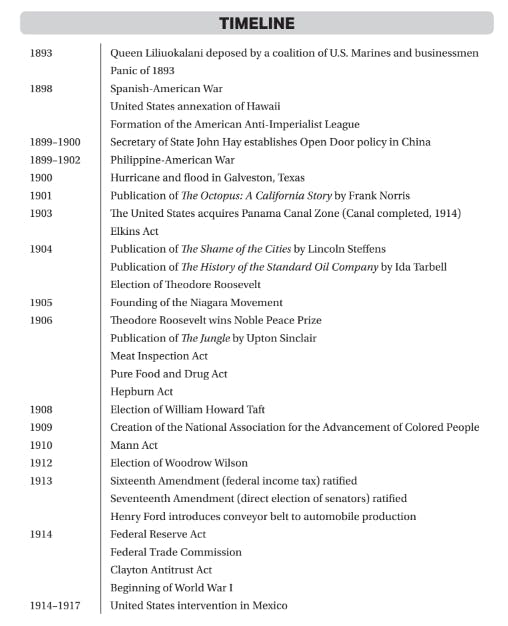

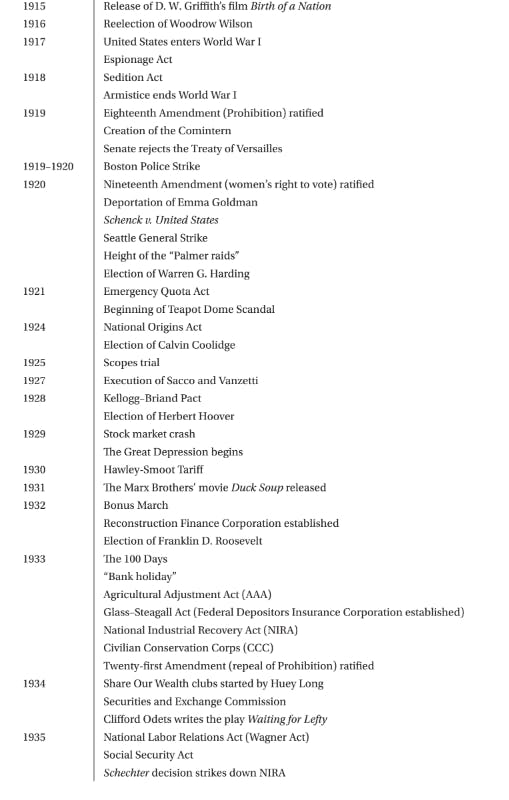

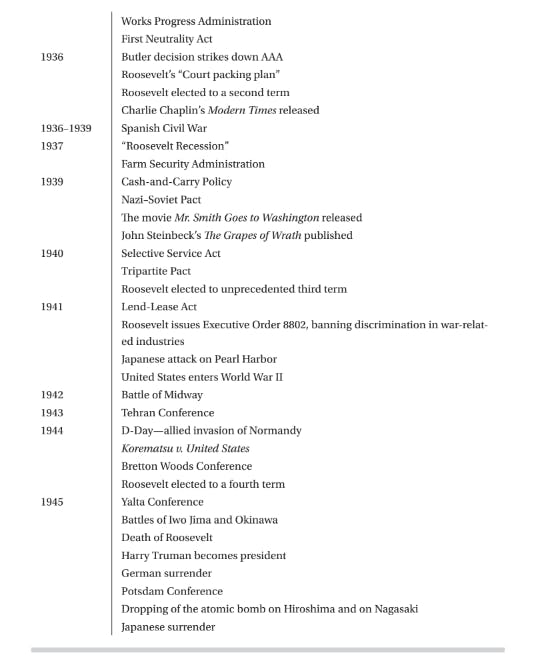

AP U.S. History Notes: Period 7 Timeline

This graphic gives a brief timeline of key events that took place during AP U.S. History Period 7.

AP U.S. History Notes: Period 7 Overview

The seventh period covered on the AP U.S. history exam took place between the years 1890-1945 and is referred to as “The Challenges of the Era of Industrialization.” The United States faced a series of profound domestic and international challenges during the period 1890 to 1945. As the country became increasingly pluralistic, Americans debated how best to meet these challenges. Debate centered on the role of the government in the economic and social life of the country and on the role of the United States on the global stage.

13 Things to Know About AP U.S. History Period 7

1. In the late 1800s, the United States entered the overseas imperialism scramble after the major European powers began carving up Africa and Asia. As America became increasingly involved in world affairs, debates ensued in the United States about the country’s proper role. Many Americans resisted the idea of the United States embarking on overseas expansion.

2. A variety of motivations factored into the United States decision to wage war against Spain in 1898. The subsequent American victory in the Spanish-American War proved to be a turning point in United States history, making it one of the world’s imperialist powers.

3. The Progressive movement developed in the late 1890s and continued through the first decades of the twentieth century. Reformers and journalists addressed a host of issues associated with the growth of an industrial society.

4. As World War I (1914–1918) began in Europe, Americans began to debate the proper role of the United States in the world. The aftermath of the war led to debates about how the United States could best pursue international interests.

5. World War I opened opportunities for employment in war-related industries, leading to significant internal migrations to urban centers. At the same time, the years during and immediately following World War I saw a backlash against the experimentation of the Progressive era and a rise in patriotism and xenophobia.

6. In many ways, the 1920s witnessed the beginnings of many elements of the modern age. Large corporations came to dominate the American economy. Improvements in technology and new manufacturing techniques led to increased production of consumer goods, greater mobility, and improved standards of living. Finally, new forms of media paved the way for a mass-media culture, while also introducing Americans to a variety of regional cultural products.

7. The 1920s witnessed a startling array of cultural and political controversies. Conflicts around national identity, immigration reform, control of the workplace, and morality pitted Americans against one another.

8. The United States economy became increasingly volatile, with major downturns following the Panic of 1893 and the Panic of 1907. The most severe downturn was the Great Depression (1929–1939). These economic downturns led to calls for greater federal regulation of the economy.

9. During the depths of the 1930s Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pushed for a series of reforms to address both the causes and effects of the economic crisis. These reforms, known as the “New Deal,” set a precedent for the federal government to play a more active role in the economic and social affairs of the nation.

10. The United States largely maintained a position of neutrality in the interwar years. It did, however, play an increasingly large role in international treaties and investment. International events in the 1930s increasingly drew the United States into world affairs.

11. In many ways, World War II required the participation of the entire American public, not simply members of the military. These efforts created a sense of unity and common cause in the country.

12. The United States, seeing participation in World War II as part of a global struggle against militarism and fascism, played an important role in the Allied victory over the Axis powers in World War II. At the same time, American participation in the war effort led to a reevaluation of ideas around race and gender.

13. With Europe and Asia ravaged from World War II, the United States emerged as the dominant power in the world. U.S. engagement in world affairs after the war was in marked contrast to its withdrawal from the international community following World War I.

AP U.S. History Notes: Key Topics in Period 7

Imperialism: Debates

- World’s Columbian Exposition: The notion of racial hierarchy accepted by most white Americans was starkly displayed at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, as a sideshow of the “exotic” peoples of the world was presented to fairgoers. These displays of “natives” were contrasted with the industry and progress of the advanced civilizations. The obvious implication was that the advances of civilization must be made available to the rest of the world.

- Missionaries: Christian missionary work went hand in hand with American expansion. Missionaries were eager to spread the gospel and introduce new populations to Christianity. Many of these missionaries targeted China’s large population.

- Hawaii: American missionaries arrived in Hawaii as early as the 1820s. Later in the century, American businessmen established massive sugar plantations, undermining the local economy. Discord between the businessmen and Queen Liliuokalani, ruler of the island, emerged after 1891.

The Spanish-American War and Its Aftermath

- The Spanish-American War: The roots of the Spanish-American War can be traced to an ongoing struggle in Cuba for independence from Spain. Three wars for independence occurred in the final decades of the 19th century (1868–1878, 1879–1880, and 1895–1898).

- The Treaty of Paris: The United States and Spain negotiated the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1898, following the war. In the treaty, Spain agreed to cede the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the United States; the United States agreed to pay Spain $20 million for these possessions.

- Open Door Policy: The United States asserted that all of China should be open to trade with all nations. U.S. secretary of state John Hay, enunciated this goal in a note to the major powers, asserting an “open door” policy for China. The United States claimed to be concerned for the territorial integrity of China, but actually was more interested in gaining a foothold in trade with China. The “open door” policy was begrudgingly accepted by the major powers.

- The Boxer Rebellion: The Boxers led a rebellion that resulted in the death of more than 30,000 Chinese converts as well as 250 foreign nuns and approximately 200 Western missionaries. The United States participated in a multinational force to rescue Westerners held hostage by the Boxers (1900).

- The Panama Canal: With the acquisition of overseas Pacific territories and with increased interest in trade with China, American policymakers wanted a shortcut to Asia. Merchant ships and naval vessels had to travel around the southern tip of South America to reach the Pacific Ocean. The building of a canal through Panama, therefore, became a major goal for Roosevelt.

- Mexican Revolution: President Woodrow Wilson became enmeshed in the twists and turns of the Mexican Revolution, which lasted through the 1910s. The revolution began with the ousting of an autocratic leader in 1910. The revolution soon degenerated into a civil war that left nearly a million Mexicans dead.

The Progressives

- The Progressive Movement: The Progressive movement was essentially a middle-class response to the excesses of rapid industrialization, political corruption, and unplanned urbanization. Not only were middle-class college graduates the primary activists in the movement, but the tone and tenor of the movement was decidedly middle class.

- Nineteenth Amendment: Perhaps the most important reform to come out of the Progressive era was the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution (1920), which gave women the right to vote. The push for women’s suffrage dates back to at least the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.

- Laissez-faire economics: Industrialists and their allies championed laissez-faire economics—the idea that the government should stay out of economic activities. By the early twentieth century, many Americans came to believe that unregulated industry could be harmful to individuals, communities, and even to the health of industrial capitalism itself.

- “Bad trusts:” President Roosevelt saw the concentration of economic power in a few hands as potentially dangerous to the economy as a whole. Although the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) was passed to limit monopolistic practices, the act was not enforced with a great deal of enthusiasm. Roosevelt made a point of using the act to pursue “bad trusts”—ones that interfered with commerce—not necessarily the biggest trusts.

- Federal Reserve Act: Many economists and reformers grew apprehensive that the viability of the nation’s financial system was in the hands of a private banker. To address these concerns Wilson pushed for passage of the Federal Reserve Act, which created the Federal Reserve System in 1913. The Federal Reserve System, which is composed of twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, is a partly privately controlled and partly publicly controlled central banking system.

- The Prohibition Movement: The movement equated the prohibition of alcohol with the quest to bring democracy to the world. The United States would purify the world of undemocratic forces and purify its citizens of corrupting alcohol. Furthermore, the anti-German sentiment that developed during World War I also played a role because many American breweries had German names. All these factors led to the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, which banned the production, sale, and transportation of alcohol as of January 1, 1920.

World War I: Military and Diplomacy

- World War I: Historians cite several developments that created an unstable, even dangerous, situation in Europe in the years before World War I. History teachers often graphically represent these factors as sticks of dynamite; the sticks, in such a drawing, are labeled “nationalism,” “imperialism,” “militarism,” and “the alliance system.”

- Franz Ferdinand: If the long-term causes of World War I are presented as sticks of dynamite, then the spark that ignited them was the assassination of the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

- Zimmerman Note: Many Americans moved toward a pro-war position after the secret “Zimmerman Note” became public in March 1917. The intercepted telegram from German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmerman indicated that Germany would help Mexico regain territory it had lost to the United States if Mexico joined the war on Germany’s side. Americans took this as a threat to their territory.

- American Expeditionary Force: The United States entered World War I late in the conflict. It did provide the Allies—Great Britain and France—with much needed reinforcement. France and Great Britain had been at war for nearly three years when the United States joined the conflict. The two million soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force proved to be crucial in Allied offensives that led to victory.

- Armistice: An armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, bringing World War I to a close. American troops suffered over 300,000 casualties, including over 50,000 battlefield deaths and over 60,000 non-combat deaths (many from the deadly “Spanish flu” epidemic that soon raged around the world).

- Fourteen Points: President Wilson put forth a document, known as the Fourteen Points (1918), which emphasized international cooperation. He envisioned a world order based on freedom of the seas, removal of barriers to trade, self-determination for European peoples, and an international organization to resolve conflicts. These ideas were rejected by the victorious European powers, with the exception of the creation of the League of Nations.

World War I: Home Front

- Espionage and Sedition Act: The Espionage and Sedition Acts were passed during World War I to put limits on public expressions of antiwar sentiment. The Espionage Act (1917) made it a crime to interfere with the draft or with the sale of war bonds, or to say anything “disloyal” about the war effort. The Sedition Act (1918) extended the reach of the Espionage Act.

- “Red Scare:” The “Red Scare,” a campaign against Communists, anarchists, and other radicals, also targeted labor leaders, attempting to portray the labor movement as a front for radical organizing. The Red Scare was a grassroots response of ordinary Americans as well as a government-orchestrated campaign.

- Nativism: Nativism, or opposition to immigration, rose sharply during World War I. Government propaganda designed to prod Americans to support the war effort frequently vilified Germans, labeling them “Huns” and portraying them as ruthless killers

- The Great Migration: The needs of industry for labor during World War I led to the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South, which lasted until the onset of the Great Depression (a second wave of the migration occurred during and after World War II).

1920s: Innovation in Communications and Technology

- Henry Ford: The most important figure in the development of new production techniques was automaker Henry Ford. In 1913 he opened a plant with a continuous conveyor belt. The belt moved the chassis of the car from worker to worker so that each did a small task in the process of assembling the final product. Although this mass-production technique reduced the price of his Model T car and made it affordable to the middle class, the assembly line dealt a blow to the skilled mechanics who had previously built automobiles.

- Advertising: The advertising industry also changed a great deal in the 1920s. Advertising and public relations men tapped into the ideas of Freudian psychology and emerging ideas around crowd psychology. Many ads in this period attempted to reach the public on a subconscious level, rather than just presenting products and services in a straightforward manner.

- The Jazz Singer: Movie attendance achieved staggering levels in the 1920s. By the end of the decade, three-fourths of the American people (roughly 90 million) were going to the movies every week. The first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer, came out in 1927.

1920’s: Cultural and Political Controversies

- “Flappers:” The new image of women during the 1920s was symbolized by the popularity of the “flappers” and their style of dress. Flappers were independent-minded young women of the 1920s who openly defied Victorian moral codes about “proper” lady-like behavior.

- The Nativist Movement: A large wave of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe had arrived in the United States between 1880 and 1920. Many Americans came to resent this wave of immigrants, fueling a popular nativist movement. There are several reasons nativists resented this new wave of immigration. Some nativists focused on the fact that most of the new immigrants were not Protestant.

- Harlem Renaissance: The Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North contributed to the Harlem Renaissance, a literary, artistic, and intellectual movement centered in the primarily Black neighborhood of Harlem, in New York City.

- “Lost Generation:” The “Lost Generation” literary movement of the 1920s expressed a general disillusionment with society, commenting on everything from the narrowness of small-town life to the rampant materialism of American society. Several writers were troubled by the destruction and seeming meaninglessness of World War I.

- The Ku Klux Klan: The original Ku Klux Klan, a violent, racist group with its roots in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, had died out in the 1880s. In the 1920s, however, the organization was a genuine mass movement. By 1925, it had grown to three million members, according to its own estimate. The Klan was devoted to white supremacy and “100 percent Americanism.” The white supremacist ideology of the Ku Klux Klan was evident in a number of race riots in the United States in the late 1910s and 1920s

The Great Depression

- Panic of 1893: The Panic of 1893 signaled the beginning of the worst economic depression in American history before the Great Depression of the 1930s. The crisis began when the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad went bankrupt; two months later the National Cordage Company also failed. These bankruptcies led to a major decline in stock prices. Because many leading banks had invested their assets in the stock market, a wave of bank failures soon followed.

- Panic of 1907: The economy took a serious downturn following the Panic of 1907. This panic involved a major fall in stock prices, which was caused by a lack of confidence in major New York banks. Several banks had invested in a scheme to gain control of the United Copper Company. When the scheme unraveled, there were runs on several of the banks that had invested large sums of money.

- “Black Thursday:” By the late 1920s, serious investors began to see that stock prices were reaching new heights as the actual earnings of major corporations were declining. This discrepancy between the price per share and the actual earnings of corporations led investors to begin selling stocks, which stimulated panic selling. Starting on October 24, 1929, “Black Thursday,” and continuing the following week, the stock market crashed, destroying many individuals’ investments.

- “Rugged Individualism:” Rather than expand federal intervention into the economy to address the dislocations of the Great Depression, President Hoover (1929–1933) invoked the idea of “rugged individualism”—the belief that the problems of the nation could best be solved by the determination and resolve of the American people.

The New Deal

- The New Deal: The Roosevelt administration developed a series of programs known collectively as the New Deal. Previously, people received assistance in times of need from churches, settlement houses, and other private charities. However, the levels of poverty and unemployment during the Great Depression were unprecedented. Roosevelt believed that the government needed to take action. The New Deal provided relief to individuals through a variety of agencies.

- Glass-Steagall Act: The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, created by the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, insures deposits so that if a bank does fold, people do not lose their savings.

- Securities and Exchange Commission: Many individuals had lost confidence in the stock market after the 1929 crash, which was partly caused by unsound fiscal practices. The Securities and Exchange Commission was created to oversee stock market operations by monitoring transactions, licensing brokers, limiting buying on margin, and prohibiting insider trading.

- Communist Party: Although the Communist Party never attracted a large following in the United States, it did gain new members and exerted influence beyond its numbers in the 1930s. Some Americans came to believe that the Great Depression was evidence that the capitalist system was simply not working. Others were impressed with the reported achievements of the Soviet Union.

- Second New Deal: With mounting pressure from a variety of populist and leftwing forces, and with a presidential election looming in 1936, Roosevelt introduced a second set of programs known as the Second New Deal. This second phase of the New Deal was less about shaping the different sectors of the economy and more about providing assistance and support to the working class.

- “Roosevelt Recession:” President Roosevelt’s move to cut spending on New Deal programs contributed in 1938 to a further downturn in economic activity, known as the “Roosevelt Recession.”

- “Dust Bowl:” From 1934 to 1937, parts of Texas, Oklahoma, and surrounding areas of the Great Plains suffered from a major drought. The area was so dry that it became known as the “Dust Bowl.” The Dust Bowl was caused by unsustainable over-farming coupled with a devastating drought. The natural grass cover of the region had been removed in the years leading up to the Dust Bowl, as wheat farmers increased the number of acres under cultivation. With this natural root system gone, the fertile topsoil simply blew away when drought struck from 1934 to 1937.

Interwar Foreign Policy

- Kellogg-Briand Pact: The United States was one of sixty-three nations to sign the Kellogg-Briand Pact, renouncing war in principle. Because the pact was negotiated outside of the League of Nations, it was unenforceable.

- Good Neighbor Policy: Upon taking office in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to pursue a more conciliatory policy in Latin America. FDR’s Good Neighbor policy was, he said, designed to create “more order in this hemisphere and less dislike.” In 1933, Secretary of State Cordell Hull signed a formal declaration, at the Inter-American Conference in Uruguay, that no nation had the right to interfere in the internal affairs of another nation.

- Isolationists: As events degenerated into armed conflicts in Europe and Asia 1930s, a debate occurred in the United States about America’s role. Isolationists argued strongly that the United States should stay out of world affairs. Many isolationists looked back to World War I as a lesson in the futility of getting involved in European affairs. The United States had lost over 100,000 men in World War I for no apparent reason, they argued. World War I had not made the world safe for democracy.

- Interventionists: Interventionists believed that the United States could no longer stand apart. Airplanes and submarines could bring the war to the United States very quickly. If Britain were defeated, there would be nothing standing between Hitler and America. Interventionists believed the Atlantic Ocean would be a means for Hitler to bring his war machine to the United States. Also, many interventionists believed the war in Europe was different from earlier European quarrels over territory or national pride. They believed that if Hitler was successful, civilization itself would be threatened. They were convinced that the Axis Powers were determined to defeat democratic forces all over the world.

- World War II: The question of the role of the United States in affairs of the world grew more intense in 1939 as World War II formally began. The war started after German dictator Adolf Hitler ordered an attack on Poland. Britain and France quickly declared war on Germany.

- Pearl Harbor: Debates about intervention ended abruptly on December 7, 1941, when Japanese warplanes attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. naval base in Hawaii. Almost immediately, the United States entered World War II. With American involvement in the war, the isolationist position was largely silenced.

World War II: Mobilization

- Office of Price Administration: During the war, there were shortages of items because of the needs of the military. Starting in 1942, the Office of Price Administration began rationing key commodities to civilians, such as gasoline and tires.

- “Rosie the Riveter:” Many recruiting posters were produced by the government, usually through the Office of War Information, showing women in industrial settings. The fictional “Rosie the Riveter” character was often featured in this public relations campaign. Female workers were presented in a positive light—helping the nation as well as supporting the men in combat abroad. Such a campaign was needed because prewar societal mores discouraged women from doing industrial work.

- Executive Order 9066: In 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing the government to remove more than 100,000 Japanese Americans from West Coast states and relocate them to distant camps in more than a dozen western states. The order applied to both Issei (Japanese Americans who had emigrated from Japan) and Nisei (native-born Japanese Americans). Most of their property was confiscated by the government. In Korematsu v. United States (1944), the Supreme Court ruled that the relocation was acceptable on the grounds of national security.

World War II: Military

- The Holocaust: The Holocaust was the systematic murder of six million European Jews and millions of other “undesirables” by the Nazis. The roots of the Holocaust pre-date World War II, with Nazi persecution of the Jews in Germany and in territories it took over in the 1930s. In 1939, Adolf Hitler and other leading Nazis developed plans for a “final solution of the Jewish question,” with the object of eliminating Europe’s Jewish populations.

- Nanjing Massacre: Europe. In 1937, Japan widened its military campaign against China, overrunning most of China’s port cities. In the city of Nanjing, Japanese troops killed thousands of civilians. While the exact number of people killed is in dispute, the Nanjing Massacre, also referred to as the Rape of Nanjing, resulted in at least 80,000 deaths and perhaps as many as 300,000.

- Battle of Midway: In June of 1942, the United States achieved a victory over the Japanese fleet in the Battle of Midway. After Midway, the United States steadily began to push Japanese forces back toward the Japanese home islands.

- D-Day: In June 1944, the Allies stormed the beaches of Normandy, France, and began pushing Hitler’s forces back toward Germany. On “D-Day” itself, June 6, nearly 200,000 Allied troops landed.

- V-E Day: By April 1945, the Soviets were on the outskirts of Hitler’s capital, Berlin, which was under devastating bombardment. On April 30, Hitler committed suicide; on May 7, Germany surrendered: “Victory in Europe Day.”

- Manhattan Project: In July 1945, just as preparations were under way for a final offensive against Japan, President Truman learned that the United States (in collaboration with Britain and Canada) had successfully tested an atomic bomb and that more bombs were ready for use. Since 1942, scientists in the top-secret Manhattan Project had been working on this terrifying and deadly weapon. The project involved several research labs at different sites. The facility at Los Alamos, New Mexico, headed by physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, was charged with construction of the bomb.

- Hiroshima & Nagasaki: The United States used this new weapon twice on Japan. On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima; on August 9, a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. As many as 226,000 people died. Soon after, on September 2, Japan officially surrendered, ending World War II.

Postwar Diplomacy

- Yalta Conference: The Yalta Conference, held in February 1945, was the most significant, and last, meeting of Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt. At Yalta, a coastal city in Crimea, the “big three” agreed to divide Germany into four military zones of occupation (the fourth zone would be occupied by France).

- Nuremberg trials: The victorious nations set up this international tribunal to try leading Nazis for waging aggressive war and for crimes against humanity. At these trials, about thirty American judges participated. Associate Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson was the chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials. Many of the Nazis defended themselves by claiming that they were merely following orders.

AP Biology Resources

- About the AP Biology Exam

- Top AP Biology Exam Strategies

- Top 5 Study Topics and Tips for the AP Biology Exam

- AP Biology Short Free-Response Questions

- AP Biology Long Free-Response Questions

AP Psychology Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP Psychology Exam?

- Top 5 Study Tips for the AP Psychology Exam

- AP Psychology Key Terms

- Top AP Psychology Exam Multiple-Choice Question Tips

- Top AP Psychology Exam Free Response Questions Tips

- AP Psychology Sample Free Response Question

AP English Language and Composition Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP English Language and Composition Exam?

- Top 5 Tips for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- Top Reading Techniques for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- How to Answer the AP English Language and Composition Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Sample Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Multiple-Choice Questions