AP U.S. History Notes: Period 2

April 10, 2024

AP U.S. History Period 2 picks up where Period 1 leaves off. Continue your test prep with our APUSH Period 2 study notes. Get a high-level overview of APUSH Period 2’s timeline and six things you should know, then take a deep dive into essential vocabulary, and key exam topics. For more APUSH test prep resources, check out Barron’s AP U.S. History Premium Test Prep Book and listen to our AP U.S. History Podcast.

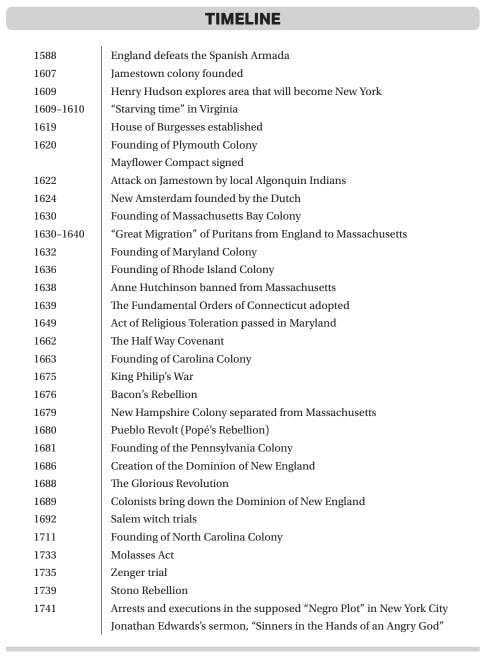

AP U.S. History Notes: Period 2 Timeline

This graphic gives a brief timeline of some of the key events that took place during AP U.S. History Period 2.

AP U.S. History Notes: Period 2 Overview

The second period covered on the AP U.S. history exam took place between the years 1607-1754 and is referred to as “Patterns of Empire and Resistance.” Throughout the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century, the major European imperial powers and various groups of American Indians maneuvered and fought for control of the North American continent. Out of these conflicts, native societies experienced dramatic changes and distinctive colonial societies emerged.

6 Things to Know About AP U.S. History Period 2

1. In the seventeenth century, several European empires competed for control of North America. These colonial powers had various priorities and goals. As they sought to exert control over different parts of North America, the Spanish, French, Dutch, and British developed various patterns for colonizing the New World. These patterns reflected the different economic and social goals, cultural assumptions, and traditions of these major powers. The different patterns were also shaped by environmental factors in North America and by competition for resources among the European powers and between them and the diverse American Indian groups.

2. Although the thirteen colonies in British North America had much in common, each of the four regions was distinct from the others. The characteristics of each of the four regions—the New England colonies, the middle colonies, the Chesapeake colonies, and the lower South and West Indian colonies—were shaped by each region’s particular geographic and environmental features.

3. The late 1600s and 1700s witnessed the growth of an Atlantic economy—one characterized by an increased exchange of goods. Colonial economies focused on selling commodities to Europe and in gaining new sources of labor. Ultimately, the growth of the Atlantic economy interactions led to an expansion of colonial economies, devastation and adaptation by American Indian groups, an increase in the use of slave labor, and changes in British mercantilist policies toward its thirteen North American colonies.

4. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, conflict intensified in North America between rival European empires and between North American colonists and American Indians. A major source of conflict in colonial North America was competition over resources—notably land and furs.

5. Slavery developed in British North America in response to the economic, demographic, and geographic characteristics of the colonies. Slavery was part of English colonial North America from the earliest years. In 1619, twenty Africans arrived in Virginia, probably as slaves. However, slavery did not become central to the southern economy until later in the seventeenth century.

6. Great Britain and its thirteen North American colonies participated in political, cultural, and economic exchanges. These exchanges led to stronger bonds between Great Britain and the colonies and reshaped the worldviews and prerogatives of British colonists in the New World. Ultimately, the priorities and interests of the thirteen colonies diverged from those of Great Britain, leading to tensions and to resistance on the part of the colonies.

AP U.S. History Notes: Key Topics in Period 2

European Colonization

- Encomienda System: The basis of Spain’s New World empire was the exploitation of the labor of native peoples. By 1550, Spain abandoned the encomienda system. Under this system, the initial Spanish settlers in the Americas were granted the right to extract labor from local inhabitants. This system led to harsh treatment of Indians.

- Repartimiento System: The Spanish government replaced the encomienda system with the repartimiento system—banning outright Indian slavery and mandating that Indian laborers be paid wages. However, Spain’s empire remained highly exploitative of native labor.

- Viceroyalty of New Spain: The northern portion of Spain’s New World empire with headquarters in Mexico City.

- Viceroyalty of Peru: The southern portion of Spain’s New World empire, consisting of Spanish holdings in South America and headquartered in Lima.

- Port Royal: The first permanent French settlements were Port Royal (1605), in what would later become Nova Scotia, and Quebec (1608), founded by Samuel de Champlain.

- Métis: Intermarriage with American Indians was common in these far-flung French colonies. The children of these marriages were known as Métis—an old French word for “mixed” or “mixed-blood.”

- The Treaty of Breda: In the seventeenth century, the Dutch obtained control of the colony of Surinam, in South America. Earlier, in the 1650s, the British had established a colony there. It was captured by a Dutch expedition in 1667 and was formally transferred to the Dutch as part of the Treaty of Breda, following the Second Anglo-Dutch War, 1665–1667. By this treaty, the Dutch formally relinquished control of New Amsterdam.

- New Amsterdam: The administrative seat, and most important settlement of New Netherland, was New Amsterdam. A settlement was established in 1624 on what is now Governor’s Island, in New York Harbor. Fort Amsterdam was soon built at the southern tip of Manhattan and a settlement was begun near the fort the following year.

- King Charles II of England: New Amsterdam became a center for the thriving trade in beaver furs and a growing commercial seaport town. However, King Charles II of England soon set his sights on the “Dutch wedge,” which divided England’s holdings in North America. The king sent a fleet of warships to New Amsterdam. The outnumbered and outgunned Stuyvesant surrendered in 1664 without a fight.

- James, the Duke of York: Charles II granted the colony of New Amsterdam to his brother James, the Duke of York, who renamed it New York. Formal transfer to the English occurred in 1667, as part of the settlement following the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

- Joint-stock Companies: Entrepreneurs established a domestic wool-processing industry, while merchants began to establish joint-stock companies, laying claim to exclusive trading rights in different regions. The Crown, guided by mercantilist principles granted charters to these joint-stock companies, such as the East India Company.

The Regions of British Colonies

- Jamestown: The first settlers to Jamestown arrived in 1607. Investors in England formed a joint-stock company, the Virginia Company, to fund the expedition. King James I chartered the company and granted territory in the New World. The Jamestown colony nearly collapsed during its first few years of existence. The colonists were not prepared to establish a community, grow crops, and sustain themselves.

- Powhatan: The local Algonquian-speaking people, led by their chief, Powhatan, father of Pocahontas, traded corn with the Jamestown settlers at first. However, when the American Indians could not supply a sufficient amount of corn for their English neighbors, the English initiated raids on Powhatan’s people.

- Tobacco: Following a difficult beginning, marked by disease, starvation, and resistance by native peoples, the colonists of Virginia began the successful cultivation of tobacco. The first shipments were sent to England in 1617. With its addictive properties, tobacco soon became extremely popular in Europe and hugely profitable for the Chesapeake Bay region. By 1700, the American colonies were exporting more than 35 million pounds of tobacco a year.

- Head-right: The leaders of the Chesapeake colonies used a variety of methods to bring workers to the New World. New immigrants were enticed to come to the Chesapeake region with the offer of 50 acres, called a head-right, upon arrival.

- Indentured Servitude: To bring lower-class agrarian workers to America, wealthy Virginians employed the system of indentured servitude. Under this system, a potential immigrant in England would agree to contract to work as an indentured servant for a certain number of years in America (usually four to seven) in exchange for free passage. An agent would then sell this contract to a planter in the colonies.

- Slavery: The first enslaved Africans were brought to Virginia in 1619. Slavery developed gradually; it was only later in the century that it began to grow dramatically.

- Puritanism: The roots of Puritanism can be found in the Protestant Reformation of the first half of the sixteenth century. Martin Luther and John Calvin both broke with the Catholic Church for theological reasons. Both argued that the Catholic Church had strayed from its spiritual mission.

- Calvinism: The Puritans took their inspiration from Calvinism. Calvinist doctrine taught that individual salvation was subject to a divine plan, rather than to the actions of individuals.

- Pilgrims: A group of separatists, known to history as the “Pilgrims,” fled England in 1608 to find a more hospitable religious climate in the Netherlands. The Netherlands, by this time, was tolerant of different beliefs and had a strong Calvinist presence, and it seemed like the ideal location for this group of English Calvinists.

- Mayflower: Slightly over a hundred separatists set sail on the Mayflower in 1620, arriving on Cape Cod. They quickly realized that they were well north of their targeted area, and did not have legal authority to settle.

- Mayflower Compact: To provide a sense of legitimacy they drew up and signed the Mayflower Compact, an agreement calling for orderly government based on the consent of the governed. The colony of Plymouth struggled the first year. By 1630, it achieved a small degree of success, but it failed to attract large numbers of mainline Puritans from England.

- Massachusetts Bay Company: In 1629, King Charles I, perhaps eager to rid England of Puritans, granted a charter to the Massachusetts Bay Company to establish a colony in the northern part of British North America. The charter did not specify the exact location of the company’s headquarters, allowing the governance of the Massachusetts Bay Company to be located in the colony instead of in England. This gave the colony a high degree of autonomy.

- Salem Witch Trials: The 1692 Salem witch trials in Massachusetts demonstrate division in the once-cohesive Puritan community. The fact that over a hundred members of the Salem community were accused of consorting with Satan speaks to the perceived lack of godly piety in New England. Also, the fact that neighbors were so ready to turn on neighbors, that men were ready to turn on women (the majority of the accused were women), and that the poorer members were ready to turn on the wealthy members all reflect a fractured community.

- Quakerism: Quakerism provided the guiding set of beliefs in the founding of Pennsylvania. Quakerism developed in the religious ferment of seventeenth-century England. Its approach to religion, and indeed to life, was radically non-hierarchical. Quakers saw one another as equals in the eyes of God.

Transatlantic Trade

- Triangle Trade: A complex trading network, developed in the 1700s, which brought manufactured items from England to both Africa and the Americas. These items included firearms, shoes, furniture, ceramics, and many other items. Kidnapped Africans were sold by human traffickers, who forced them into the international slave trade.

- The Slave Trade: The slave trade not only resulted in kidnapping, but it also worsened ethnic and societal tensions and served to destabilize the region. The victims of the slave trade were from a variety of cultural and linguistic groups. These Africans—mostly young and male, with men outnumbering women two to one—were next transported to the New World in horrid conditions.

- Fur Trade: A lucrative fur trade drew French, Dutch, and English traders and colonists to the interior of the North American continent—specifically the broad swath of land stretching north from the Ohio River toward the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes. This fur trade led Europeans to reach accommodations with American Indian groups, in contrast to the agricultural settlements along the Atlantic Coast, where American Indians were often exterminated or removed.

- Mercantilism: Britain’s ambitions in the New World were influenced by mercantilism—a set of economic and political ideas that shaped colonial policy for the major powers in the early modern world. Mercantilism holds that only a limited amount of wealth exists in the world. Nations increase their power by increasing their share of the world’s wealth.

- Navigation Acts: From the 1650s until the American Revolution, Britain’s Parliament passed a number of Navigation Acts. The goal of the acts, in conformity with mercantilist principles, was to define the colonies as suppliers of raw materials to Britain and as markets for British manufactured items. Toward this end, Parliament developed a list of “enumerated goods”—goods from the colonies that could be shipped only to Britain.

- The Glorious Revolution: Protestant parliamentarians rose up in the “Glorious Revolution” (1688), inviting William and Mary to become England’s monarchs. King James was deposed in this bloodless uprising. The Glorious Revolution empowered Parliament and ended absolute monarchy in England. It also led to the establishment of the English Bill of Rights.

Interactions Between American Indians and Europeans

- The Beaver Wars: The Beaver Wars, an especially deadly series of events in the middle and late seventeenth century, illustrate the destabilizing influence of trade and European firepower on American Indian relations. Competition in the fur trade, as the name of the wars implies, led to violent conflict. By 1645, long-simmering tensions between the Dutch-allied Iroquois and the French-allied Algonquian-speaking tribes of the Great Lakes region, notably the Huron, exploded into open warfare.

- King William’s War: King William’s War was the New World manifestation of the Nine Years’ War in Europe between France and an alliance of countries, that included Great Britain. The war in the New World had two sources. First, tensions between American Indian groups allied with the British (including the Iroquois Confederacy) and those allied with the French led to fighting in New York and Canada. Second, skirmishes occurred when British colonists encroached upon the French colony of Acadia (which included present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Maine north of the Kennebec River).

- Queen Anne’s War: Queen Anne’s War occurred on the border with Canada and in the American South. In the North, French and British forces continued the struggle for territory as they had earlier in King William’s War. Fighting in the North included a bold and destructive raid by the Wabanaki Confederacy, with French support, on Deerfield, Massachusetts. In the South, European powers and allied American Indian groups fought for control of territory.

- King George’s War: The third conflict between the French and the British, King George’s War (1744–1748), was fought in New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Nova Scotia. The war included a successful siege by New England soldiers on the newly built French Fortress of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia. French and Indian forces destroyed Saratoga, New York.

- The Pequot War: The colonies of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth worked in alliance with each other and with the Narragansett and the Mohegan peoples to defeat the Pequots. Later, further warfare would virtually eliminate a cohesive native presence from New England.

- King Philip’s War: The catalyst for combat was the 1675 execution of three Wampanoags who had been tried in a Plymouth court for killing a Christianized Wampanoag. The chief of the Wampanoag, Metacomet, also known to whites as “King Philip,” launched an attack on a string of Massachusetts towns. Several towns were destroyed and over a thousand colonists were killed. The counterattack by the New Englanders was fierce. They received crucial support from the Mohawks, who were longtime foes of the Wampanoags. By the spring of 1676, over 40 percent of the Wampanoag were killed. The war was catastrophic for both sides— it was the deadliest of the wars of European settlement in North America in regard to the percentage of the populations of each side killed.

- Pueblo Revolt: By the second half of the seventeenth century, Pueblo Indians in New Mexico had grown increasingly resentful of Spanish rule. In 1680, these grievances came to the surface in the Pueblo Revolt, also known as Popé’s Rebellion. The rebellion was centered in Santa Fe and resulted in attacks on Spanish Franciscan priests as well as ordinary Spaniards. More than 300 Spaniards were killed.

Slavery in the British Colonies

- Bacon’s Rebellion: In 1676, frontier tensions erupted into a full-scale rebellion, known as Bacon’s Rebellion. Nathaniel Bacon, a lower-level planter, championed the cause of the frontier farmers and became their leader.

- The Stono Rebellion: The most prominent slave rebellion of the colonial period was the Stono, South Carolina, rebellion in 1739. The rebellion, initiated by 20 slaves who obtained weapons by attacking a country store, led to the deaths of 20 slave owners and the plundering of half a dozen plantations. But the rebellion was quickly put down and the participants beheaded with their heads placed on mileposts along the road.

Colonial Society and Culture

- The Great Awakening: Protestant leaders in colonial America faced several challenges in the early 1700s, notably a decline in church membership and a lessening of religious zeal, as well as the rise of Enlightenment philosophy which challenged religious orthodoxy. By the 1730s, several charismatic ministers sought to take action and infuse a new passion into religious practice. These ministers and their followers were part of a religious resurgence known as the “Great Awakening.”

- Deism: In the 1700s, many educated colonists moved away from the rigid doctrines of Puritanism and other faiths and adopted a form of worship known as deism. In a deist cosmology, God is seen as a distant entity. Deists did not see God intervening in the day-to-day affairs of humanity. God had created the world and had also created a series of natural laws to govern it.

- Religious Toleration: The idea of religious toleration—allowing religious groups outside of the official, or established, religion to practice freely—had European roots and New World manifestations. In both the Old World and the New World, the concept was the object of much debate and contestation.

- John Locke: Many colonists who challenged imperial control drew on the political thought of the Enlightenment. John Locke, the British political theorist, was widely read in the colonies. He insisted that the primary role of government was to protect certain “natural rights”—including life, liberty, and property.

- Cato: “Cato” was the pseudonym for the writing team of John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon. They borrowed the name from the foe of Julius Caesar who passionately defended republican values. The essays, labeled “Cato’s Letters,” were first published between 1720 and 1723 in British newspapers and were frequently reprinted in the colonies. “Cato’s Letters,” later collected in the volume Essays on Liberty, Civil and Religious, condemned corruption within the British political system and warned against tyrannical rule.

AP Biology Resources

- About the AP Biology Exam

- Top AP Biology Exam Strategies

- Top 5 Study Topics and Tips for the AP Biology Exam

- AP Biology Short Free-Response Questions

- AP Biology Long Free-Response Questions

AP Psychology Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP Psychology Exam?

- Top 5 Study Tips for the AP Psychology Exam

- AP Psychology Key Terms

- Top AP Psychology Exam Multiple-Choice Question Tips

- Top AP Psychology Exam Free Response Questions Tips

- AP Psychology Sample Free Response Question

AP English Language and Composition Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP English Language and Composition Exam?

- Top 5 Tips for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- Top Reading Techniques for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- How to Answer the AP English Language and Composition Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Sample Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Multiple-Choice Questions